WHAT ARE THE CAUSES OF CHANGE

– Chapter 2 –

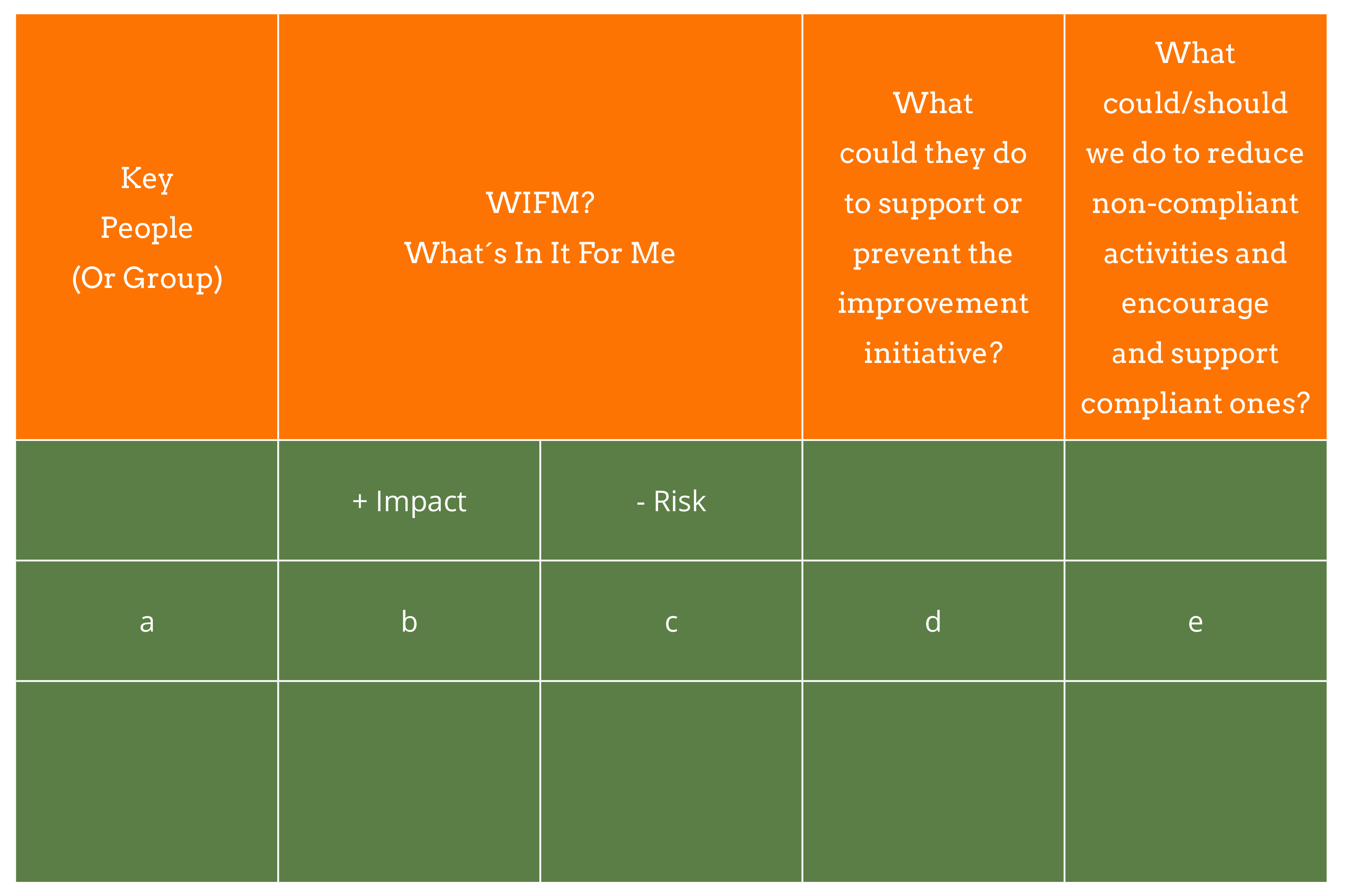

To manage change well, you need to recognise and understand the human variables. Then gain support and commitment from those affected by the change

There are many models for change out there with many overlapping concepts. In this section I’ll examine an investigate what are the causes of change.

Default approaches to change management

When it comes to organisational change, what is the most common thing you’ll hear people say? Usually it’s something like “change is hard.”

There are some good reasons why people perceive change to be hard. For the most part it’s because they’re using the wrong model. They’re using the default model of change. The default model is motivation (Carrot & Stick) + Information will get people to change.

In this section I’ll look at the default model in detail.

The default model of change

Carrot & Stick approach

As I said in chapter one, change is about getting people to change their behaviour. The most common approach is to ask them to do X instead of Y. Then establishing standards and regulations, punishing failures with fines.

Now, punishments can and do work. But psychologists have shown, when presented with negative consequences, people tend to give up.

The opposite side is incentives

Again, there is a place for incentives to motivate behaviour. But, incentives are much harder to put in place than most people think. To do it well, a sophisticated tracking and monitoring system is required.

Think of sales, the traditional space where incentives in the form of commissions have existed for years. Dan Pink’s book on motivation, Drive, laid that one to rest. He showed research that commissions don’t work as well as expected and are inferior compared to base pay.

Pink showed commissions are effective as incentives for piece work. Piece work has clear objectives and little ambiguity. But hardly the stuff of the modern organisation.

As change managers, what we’re after is creating a culture where people take up the desired behaviour of their own volition. Even when no one is watching. Day in day out.

So, what is “culture?”

The best definition of culture i have come across is “culture is the set of beliefs that directs behaviour.” Coming from the default model of change, most managers attempt the direct approach to changing behaviour. When instead they should be looking to tap into peoples beliefs.

Normative (peer) pressure

The other approach is to try and motivate people by telling them that others are doing it, and so should you. Psychologists call it “normative pressure”; your mother would have called it “peer pressure.”

A few years into the workforce, I was earning a little money and the company I worked for held ‘free’ meetings with their financial planners (who would pay for a meeting with a sales person?). I was told everyone was doing it and so should I.

Upon casual conversation with my colleagues, I found out that he had given the same reasoning to everyone. In fact, had not actually signed up. In sum, missing out was not such a big deal after all and I decided to drop out before the penalty period.

This is why marketers use testimonials. Studies show that people are easily coerced into selecting the stick that is clearly smaller. All the while others say it is the same size and we deny our own senses in order to conform with others.

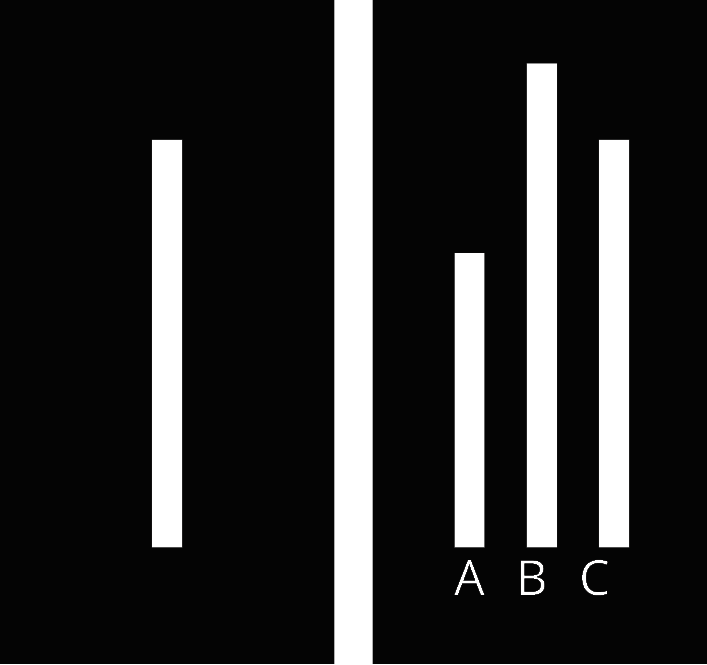

In a now famous experiment, psychologist SOLOMON ASCH asked subjects to indicate

which of the three lines from the second image is the same length as the line in the image on

the left.

The correct answer is C. But his experiments showed that bright and assured people could be “manipulated” into giving the wrong answer. Nine experiment participants were shown the above image and were asked to call out which line on the right was the same length as the one on the left.

The researchers ran the experiment 12 times, in each round only one of the nine participants was actually tested. The other eight were “plants” and told to purposefully call out incorrect answers.

The result?

Seventy six percent of participants tested denied their own senses at least once, choosing either A or B. And one-third of the time, the one who was actually tested conformed to what the crowd thought.

This is the nature and power of normative pressure.

There are a variety of reasons for this. These include fear of disapproval, self-consciousness and not wanting to stand out or be different.

But while it can be powerful, it’s fickle. As soon as the charade is revealed, people stop complying, furthering its fickleness and the intended consequences are not always as desired.

I once worked in a call centre where I had to work weekends. Loafing in righteous indignation, there was a little productivity at a high cost because the boss wasn’t there and the supervisors didn’t want to be either. We were physically present but not mentally.

Contrast this to working for myself where I’d think nothing of working on a weekend. This difference is I love this work, I create my own life, and I am empowered to work as I want. I own all the outcomes, good or bad.

That’s the essence of empowerment. Most people who aspire to be self-employed and entrepreneurs are thinking of this kind of freedom as proper motivation.

But if you’re in it just for the money rather than for passion of the craft and work itself, you’re in no better position. Making money can be a great motivator for individuals and companies but once the basic needs are met, it no longer serves as a motivator.

The same is true for normative pressure. It can work when aligned to our self-interest, but stops abruptly when it is no longer sustained.

The core problem of change

If Maslow’s hierarchy is true, it makes sense that people are pursuing an ever growing sense of productivity and happiness.

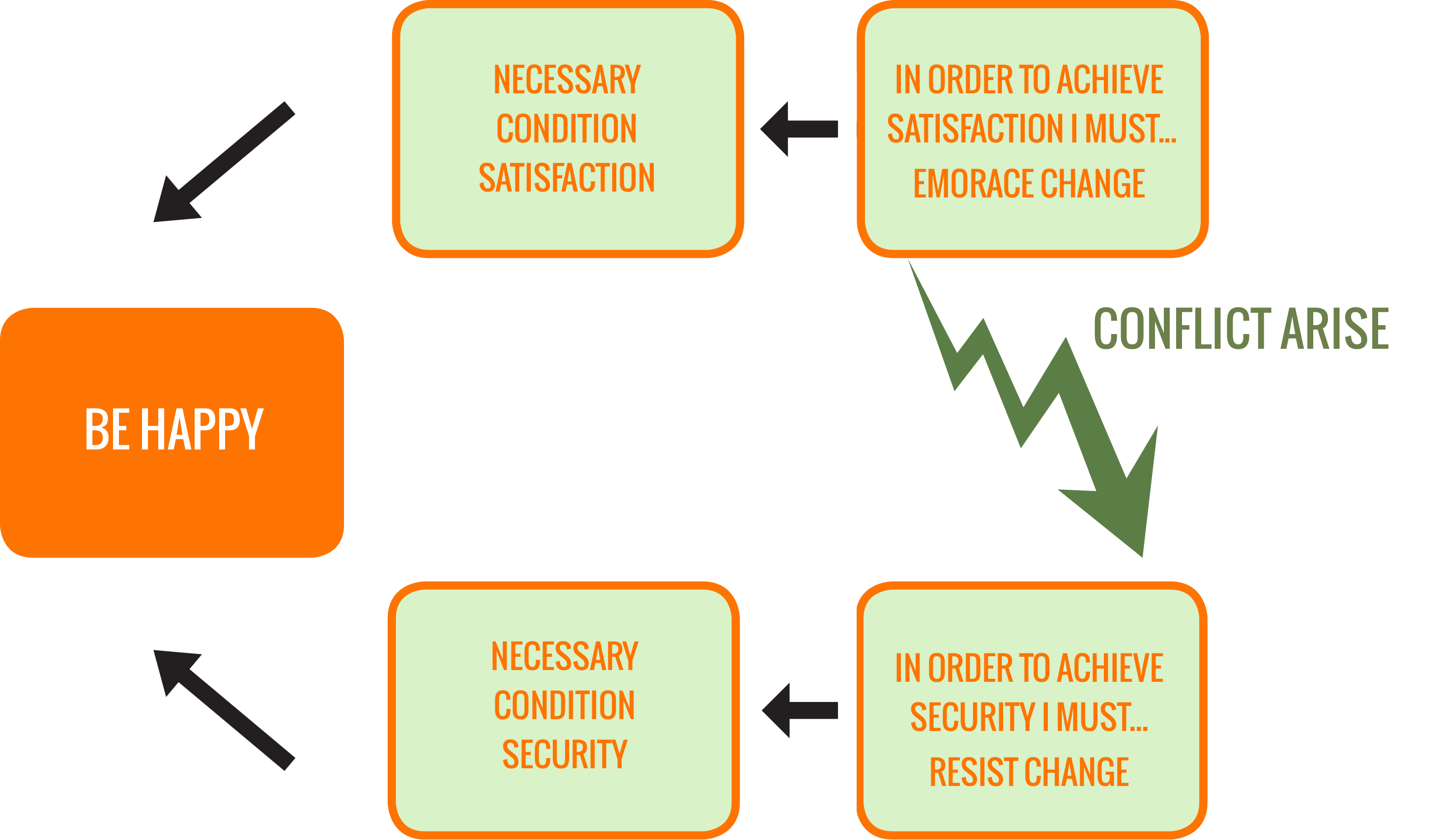

One of the most interesting and succinct models about how people go about his came from a psychologist, Efrat Goldrat. In the early 1990s Effrat put forward the idea that for people to achieve happiness, they must satisfy two necessary conditions, security and satisfaction.

It makes sense that people feel happy with their lives when they feel secure and have predictability about future events. Large uncertainty about the future produces anxiety and decreases happiness.

Goldratt also defined satisfaction as that which one feels after having achieved a challenging goal that was in doubt.

But we can see that these two necessary conditions, while parts of Maslow’s hierarchy, are actually in conflict with each other.

To achieve satisfaction we must embrace change, but to have security we must resist change.

This is a terrific insight. if we’re to move people through change we must understand the dilemma people face. These dilemma’s are what weights them in indecision.

Often people may say they want and embrace change but they’re actually not behaving that way. It’s vexing because often they don’t understand either.

So with a bit of theory guiding us, how do you cause the change?

Effrat´s cloud: a conflict arise based on peoples need to have both security and satisfaction at the same time.

Effrat´s cloud: a conflict arise based on peoples need to have both security and satisfaction at the same time.

Making change happen

Enlightened self-interest

If you’ve ever had to manage people, you’ll know the pain and amount of time it takes manage employees who don’t want to be there.

You don’t need lots of rules and performance management systems to manage these people.

Yet, when you hire the right people, you don’t need any of it.

When people change, it’s because they want to change. You benefit from the following:

- You don’t need to be constantly there to watch for the behaviour you’d like to see. It expensive and time consuming.

- Quality of performance remains high and self-correcting.

- They’re enthusiastic about the work. And nothing beats genuine enthusiasm; it becomes contagious.

- Motivated people are more likely to change and improve in the future. People pursuing self-directed goals are more likely to see opportunities for improvement, and more likely to change in the future.

A case study:

Take the example of Lou Gerstner when made CEO of IBM in 1993, taking the reins of an old and prestigious institution with a rich history. Gerstner had no computer industry experience, but he did have deep leadership experience.

And he would need every bit of it taking over IBM. The company had recently suffered a multibillion dollar loss and was burning cash.

The company had recently suffered a multibillion dollar loss and was burning cash.

“There’s been a lot of speculation as to when I’m going to deliver a vision of IBM [but] the last thing IBM needs right now is a vision,” Gerstner said at his first press conference. He needed to make some tough decisions and get his new team members working together effectively – fast.

Gerstener turned IBM away from the brink of bankruptcy. Changed the company into a service and consulting business that is still thriving today. Corporations all over the world are using IBM as their outsourced technology providers.

But the question remains: How did he motivate his workforce to come together in those dark days?

To answer that question, let’s turn our attention to an example from history about why one innovation spread, but the other seemingly equally beneficial did not.

How beliefs drive behaviour

People don’t resist change, people resist what they believe isn’t the right thing to do.

This is a critical distinction. As we just covered in the sections above, more information and external motivation isn’t what makes the difference.

Doctors, dentists and behaviour change

To understand how people’s beliefs, rational or otherwise, are intertwined with behaviour, consider the following story told by Atul Gawande in an article, Slow Ideas, he wrote for the New Yorker, from the annals of medical history.

How beliefs drive behaviour Medicine in the mid-1800’s was pretty awful. Awful for the patient of course, having their legs cut off say. And no doubt for the doctor doing the dirty work.

In 1846, a little known dentist used a gas to numb a patients while he pulled out a tooth from his mouth. This caught the attention of another doctor and who published this in a medical journal.

The approach of using gas to numb patients took off in all fields of medicine. There were pockets if resistance Gwande reports. Preachers and ministers said the use of pain medication in child birth was “frustrating the designs of the almighty”.

Contrast this to the solution to combat infection in the same operating theatres around the same period in time. Around this time you were more likely to die from the infection rather than the operation itself.

In the 1860s, an Edinburgh surgeon named Joseph Lister read a paper by Louis Pasteur, a French chemist and microbiologist. Pasteur discovered that spoiling and fermentation were the consequence of microorganisms, or bacteria.

Lister investigated further and discovered that a solution of carbolic acid would kill off the bacteria. He reasoned that if doctors would wash their hands in this solution, infection and the needless deaths it caused, could be prevented.

And of course the doctors took this innovation with enthusiasm, right? Wrong. It would be another fifty or so years before washing hands became anywhere near common practice. Even today it remains an issue.

Motivation is intrinsic

There are a lot of requests for motivators in coaching and consulting. Sales managers want their team members motivated and companies will hire you to motivate them. But you can’t.

Lou Gerstner couldn’t “motivate” his people. The advocates for doctors washing their hands could not motivate surgeons. And I can’t motivate you.

Motivation is intrinsic: we motivate ourselves. This is because what drive motivation is our own individual values and beliefs. To illustrate the truth of this, consider how some people are motivated by power or recognition, and others by independence. The point is everyone is different and blanket approaches don’t work.

It’s often assumed that money is the ultimate motivator. But in reality, cold hard cash motivates few people. Mintz Hertzberg, one of the pioneers of motivation theory, found that for most people, pay is a hygiene factor.

That is, the absence of money is a huge demotivator. Once an acceptable limit is reached, any more has diminishing returns. Throwing money at unhappy employees just makes them richer, yet still unmotivated employees.

SO IF MONEY IS NOT A MAIN MOTIVATOR, WHAT IS?

This is where our doctors come back in.

Why was it so easy for anaesthesia use to spread among dentists, yet surgeons refused to wash their hands?

The innovation of anaesthesia solved the visible and present problem of patient pain. Washing hands solved an invisible problem of germs and the results were not seen for some time down the line.

Anaesthesia though improved the experience of the doctor as well as the patient.

The washing of hands required doctors to douse themselves in carbolic acid. This was a painful and labour intensive process for the doctors. Combined with the lack of visibility of results it’s easy to see how they resisted the change.

The difference is rational self-interest. Which isn’t always obvious or rational (depending on your perspective). But with some prying we can find it out.

–

When you change the beliefs that are restricting peoples world view you open new possibilities for action.

–

Reciprocity of values

In the daily to and fro of organisational life, we all share differing business and personal goals and self-interests. Perhaps the incentives of the sales manager are cost management and so has the sales people enter their expense reports on time.

The manager might take time to understand the best way to reward one member. Perhaps it’s team recognition over cash. Thus, an exchange of values is made and self-interest maintained throughout.

Employees understand and respect the manager’s self-interest as they do theirs. In a large dynamic and diverse organisation, it is important to understand what is driving people to do what they do. Avoid blanket reward and recognition programs or any other unilateral program of this nature.

Don’t set up competitions where people win and lose. Instead, foster an environment where everyone can improve over last years results.

HOW DO YOU FIND OUT PEOPLES BELIEFS AND VALUES?

- Ask them: both in professional sense and personal on a casual level.

- Listen to their language: especially the examples they use. I had a manager who made sporting analogies to explain business issues. He was a football coach and having the kind of career that gave him that flexibility was important.

- Watch their behaviour: are they better when given lots of autonomy or do they need more of your time? Do like giving presentations or avoid the limelight?

- Analyse their successes and failures: with them in coaching and mentoring sessions. When did they perform well and when did they perform poorly?

All these can apply at global level too. Using surveys, focus groups and one-on-one interviews, you’ll find out what’s been bothering people, and what’s been getting in the way of self-directed productivity. Target these issues when designing your change approach and key messages.

Never confuse others self-interest for your own. I have a friend, a software developer, who loves to work all through the night. He works for himself and successfully at that. But when he was an employee, he did poorly.

He just couldn‘t work in the 9-5 environment. What motivates us, stable working hours for this example, doesn‘t always motivate others. That’s why, as managers, it’s so important to understand the underlying values and beliefs that motivates others.

Finally, sometimes others self-interest is not in the organisation’s interest. In these rare cases people should be moved on. When I was a manager, I fired an employee after repeated attempts and coaching and training.

The reality was she could actually do the work, so more training was not going to help the situation. The problem was one of attitude.

Coaching can sometime help attitude problems, but in the end she had to ‘want to do the work’. Values inform attitude and hers were not aligned. She came in late one day (huge issue in a time-sensitive business) and I fired her on the spot. The minute she walked out of the door, the remaining team members all gave a sigh of relief.